Dark Matter, MOND, and a Confusion of Categories

Dark matter is one of the most discussed topics in popular science, often framed with the clickbait: "Was Einstein Wrong?" Well, no. No, he wasn’t.

This is Betteridge's Law of Headlines, and in general, articles about gravity fall into a few predictable categories: the above clickbait, "Shock: Einstein Proven Correct Again!", and, at more than one talk, I’ve been asked, “Dark Matter or MOND?” MOND (Modified Newtonian Dynamics) is something of an internet darling, often presented as an alternative to general relativity.

As we’ll see, that’s a category confusion.

This framing misleads the public, blending distinct concepts—observable phenomena, models, laws, and theories—into one muddled question with seemingly simple answers.

The scientific community isn’t debating whether dark matter exists—only its amount and form. And while there’s ongoing discussion about gravity’s nature, MOND isn’t really part of it.

I can’t say this confusion is accidental. But if you’ll indulge me in a few definitions, you’ll quickly see why the premise is flawed—and how the very clearly interested general public is being misserved by media hyping a controversy that doesn’t exist.

Models and Laws

We'll start with model, which Wikipedia defines as "... an informative representation of an object, person, or system." We're more interested in mathematical models here, which it defines as "... an abstract description of a concrete system using mathematical concepts and language" and goes on to break down a traditional mathematical model into governing equations, sub-models, and assumptions. For now, we can be more specific: A model is given by an equation and a domain of relevance. That equation might have many parameters that each need explaining, but the idea you should have in your mind is a fairly simple, short, but precise top-level description in mathematical notation along with the precise conditions when it is relevant.

We build models all the time, for everything, but a specific kind of model is the law. A law is an empirically derived model that, after taking into account noise, exactly replicates measured data. Think of Ohm's Law: $$V = I R$$ where $V$ is voltage, $I$ is current, and $R$ is resistance. Of relevance here is Newton's Law of Gravity: $$\vec{F} = - G\frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\vec{r}$$ where $\vec{F}$ is the force, $G$ is Newton's constant, $m_1$ and $m_2$ are the masses, $r$ is the distance between the masses, and $\vec{r}$ is the direction between the masses.

The laws of physics can't be changed (Jim), and if a law appears not to hold, it is usually because it is being used outside its domain of relevance. For example, the existence of superconductivity at very low temperatures doesn't invalidate Ohm's Law at normal temperatures.

The important thing about a law is that it has Predictive Power. Given some input information, within its domain of relevance, a law predicts exactly what you will measure reality to be.

And this leads straight into our first category confusion:

Law vs. Theory

Newton's theory of gravity is that it exists (and follows a law). That's it. Now, it was a huge leap of faith to say that there is an invisible force between celestial objects (that obeys his Law of Gravity), but that's the extent of it.

General Relativity is a somewhat more substantial theory that derives a force law from the ideas of curved space-time, and in the low-gravity, low-speed world we normally observe, it replicates Newton's Law just fine. So, General Relativity doesn't invalidate Newton's Law of Gravitation, but it does start adding correction terms to extend its domain of relevance. The simplest of these gives: $$\GRB$$ where $c$ is the speed of light, and $\vec{v}$ is the relative velocity of the masses.

This really isn't how you should use GR! But hopefully, you can see how Newton's Law and Einstein's Theory relate to each other. Normally, when we are discussing these things, it is not necessary to be pedantic, as it's easily understood what model, law, or theory is being referred to by context. However, when people are being misled, well, then it isn't pedantry—it's accuracy and discipline.

A good theory has Explanatory Power. As well as predicting laws and agreeing with measurement, it tells you something about why the laws are the way they are, hopefully with some general principle. For example, General Relativity uncovers the principle of least spacetime interval, where free-falling objects and light follow geodesics determined by said interval on a curved spacetime.

Which leads us into what is probably the worst-named problem in astrophysics:

The Dark Matter Problem

Galaxies are big, and galactic clusters are bigger, and the distances between objects are vast. Which means the timescales on which things happen in galaxies are, well, not on a human timescale. We have lots of measurements of stars and galaxies and how they are moving right now, but if we (humans) want to understand how these vast structures evolve over time, we have to build simulations based on these observations and the models we have to describe our universe.

So that's what we did. Initially, just using Newton's Laws, we built simulations of galaxies and clusters using a mass inventory formed from estimates of the number of stars (bright matter we can observe) and informed guesstimates of things like black holes, planets, and dust (dark matter we cannot observe).

And the simulations didn't match observation.

It is a core tenet of science that if your results do not match verified measurements, then you got something wrong in your model, simulation, hypothesis, etc. Nature really doesn't care what you like or think—if it doesn't match measurements, then it's wrong.

Even if you use GR as the model and theory for gravity, the results don't work out.

So now we have a serious tension. Either GR, arguably the most tested theory humans have produced, where every direct experiment and the many indirect experiments are constantly proving that Einstein was correct, is in fact broken in a non-trivial way, or we got our mass inventory guesstimates wrong. There are many such measurements now, and of very different types, and all of them can be fixed by fairly simple additions to the mass inventory.

It takes quite an ego to assume Einstein got it wrong, but the amount of matter often needed to correct the inventory is huge. Sometimes you need 5 or 6 times the observable matter as unobservable matter, and it is distributed in an uncomfortably uniform and symmetric manner to get the simulation to match measurements. This is extraordinary and requires extraordinary evidence, which we now have, but at the time, it was a big problem labeled 'The Missing Mass Problem,' 'The Rotation Curve Problem,' or 'The Dark Matter Problem.'

First Principles

If you go back to first principles and take the data seriously, you can empirically derive laws for all the various measurements. These require a few extra parameters, all of which are unique to each measurement unless you also tune the matter inventory. Arguably the most important of these is Milgrom's law because it is the law upon which MOND is based.

You can back out a full theory from Milgrom's law—that is, one that meets all the other consistency requirements for the simulations to work. However, the only evidence for that is Milgrom's law itself because, well, it's an empirically derived law.

MOND, then, is a simulation or larger model based on a law, NOT a theory, though you can call the larger construction a theory because, circularly, it'll match measurements by construction via Milgrom's law. So, just like Newton's theory of gravity is that it exists and follows a law, MOND's theory of gravity is that it exists and follows Milgrom's law. Unlike GR, neither says anything about why, that is, they have little to no explanatory power.

This is also why MOND is considered interesting-but-not-relevant by all of the theorists I know. Instead of starting with some premise and deriving a prediction that matches measurements, you construct any system from which Milgrom's law can be derived and upgrade it to a 'theory' because it agrees with the measurements you constructed it to agree with. It doesn't really add anything to the discussion.

So the tension remains: either we need more matter, or sometimes gravity is modified. Let's take matter first.

The Theory of Dark Matter

We know black holes and other dark matter, like planets and dust, exist. So the problem isn't the existence of dark matter, but the amount of it and the ratio of the various types. Every anomalous observation can be explained by adding some amount of dark matter to the matter inventory—which makes dark matter as a theory not very explanatory and not at all satisfying—not that Nature cares.

Except that the structure of the matter added is always in some uniform and symmetrical shape—so how did that happen!?

One answer is that much of the dark matter is massive but only interacts via gravity or possibly the weak force, or something weaker. Despite many possibilities and a lot of looking, we've yet to find anything that fits that description.

And the more possibilities we rule out, the more the pendulum swings back toward the second option.

A quick note before we move on: you can add the matter to the inventory either in the simulation or by baking it into the theory directly so that the derived forces work correctly. This latter is not modifying gravity, even if you hide it carefully and get away with publishing it; it's just adding dark matter by another name.

So,

Modifying Gravity

Doesn't work.

No, seriously. There are hundreds of papers from dozens of institutions attempting to modify GR in such a way as to match Milgrom's law, and every one describes a universe in which we do not live. That is, they predict things we do not see, and would see quite easily. While there are lots of interesting ideas, none of these, over decades of work, has succeeded.

Now, that doesn't mean we shouldn't keep looking or trying—we know, after all, that we don't have a good theory of quantum gravity yet. But it would be nice if just some of those papers were read before people declare the existence of dark matter obviously wrong and Einstein in error.

Conclusion

I think we've lost something important in the attempt to simplify the "Dark Matter Problem" for science-communication purposes, and that it has led to a misrepresentation of the scientific consensus on what is happening.

I also think that some are using this misunderstanding to hype a controversy that doesn't exist in order to capture attention—to great effect, I might add!

The reality is that the evidence for dark matter as the solution to the Dark Matter Problem is pretty overwhelming at this point. However, we shouldn't stop looking for alternatives because our search for dark matter candidates has, up to this point, been singularly unsuccessful.

And there are other possibilities, like the simulations being too simplistic on the scale of galaxies and clusters (Google 'baryonic feedback'), or wilder ideas like modifying inertia, or the existence of a Dark Fluid.

But anyone who tells you that MOND is the answer is suffering from category confusion. Einstein wasn't wrong, and MOND isn't helpful.

If you'd like to see the theme of this article but from a more experimentalist's perspective, I highly recommend Angela Collier's irreverent dark matter is not a theory and its brilliant follow-up What we have here is a failure to communicate.

If you would like to explore other ideas for gravity, consider Erik Verlinde's awesome Entropic gravity or Jonathan Oppenheim's spectacular A Postquantum Theory of Classical Gravity?.

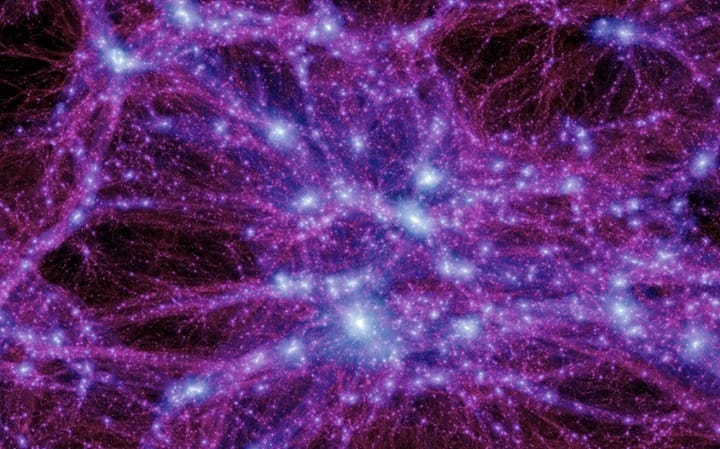

The cover image is from the wikimedia commons.

\newcommand\GRB{F=-G\frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\vec{r}+3G\frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\frac{\vec{v}\bullet\vec{r}}{c^2}\vec{r}+\cdots}